Here’s a quick one for the start of the year:

Winter fails to come or sort of comes, or comes and then backs off, later and later every year… in northern New England where we live even late December isn’t reliably winter now. A massive and almost tropical storm came through the Northeast about a week before Christmas, thawing mountainsides and the limited snowpack and flooding rivers and creeks in Vermont, New Hampshire, and elsewhere up north. It was the highest I’ve seen Vermont’s White River since I’ve lived near it but that doesn’t compare to the insane flooding recorded in Jackson, New Hampshire:

Or for that matter the Mad River not terribly far away in the lovely town of Waitsfield:

It wasn’t as bad for much of Vermont as this summer’s July flooding but it’s yet more evidence that our infrastructure is fundamentally unable to handle the climatic stressors that are occurring more and more frequently. Here’s VTDigger on the increasing probability of winter flooding:

“Say you get like two inches from the sky, and you might also get two inches from the ground itself, like the snowpack itself, (then) you’re not really talking about a two-inch storm. You’re talking about a four-inch storm,” [Jonathan Winter, associate professor of geography at Dartmouth College] said.

And a four-inch storm is much harder to handle than a two-inch storm, especially when the ground was already saturated from previous precipitation in the past few weeks.

“When we make our forecasts about flooding — you know, like flooding from rivers, like rivers coming up over their banks — there’s a lot of variables there. It becomes half art, half science,” Winter said.

And there are attendant impacts, like the risk of spring flooding of Lake Champlain:

But the new variability and extremes extend across all seasons. Our roads, bridges, electrical and water systems, building codes, agricultural practices, and on and on and on—these are predicated on a stability that is now disappearing. Will it fully disappear?

In my last post I predicted impending rain but I was actually about a week early. I kept a sort of intermittent weather diary during that first weird storm which turned out to be mainly snow:

Dec 10

The rain is switching over to snow (nearly midnight)

The ground which has been trying to freeze has this weird hard spongy consistency. It’s been raining for a few hours and was nearly 60° today

Dec 11

Woke up to a landscape completely white, maybe four inches of thick wet snow—wet enough to thickly coat and weigh down all the tree branches, not so wet that it’s (yet) dripping off in clumps. Wet and heavy to shovel but the birds are going for the feeders and so far the winds aren’t too bad, but they’re supposed to pick up later today [they didn’t, thankfully, so we didn’t have to worry extra about the over-loaded branches coming down]

I wrote this and then thought I’d keep this diary going but I didn’t. But I can tell you what happened, loosely: it cooled off, then it got warmer and on December 18 we saw the rain and flooding I mentioned above, then little rivulets everywhere and rapidly flowing streams as it cooled again and at first a thin crunchy layer of ice formed on everything and then it cooled more and the ice became thick and slick until walking outside in many places was a hazard.

Then there was a quite nice, light and fluffy dusting of snow Christmas Eve morning… but then we came down to New York where it’s even warmer and wetter, where winter really doesn’t come anymore.

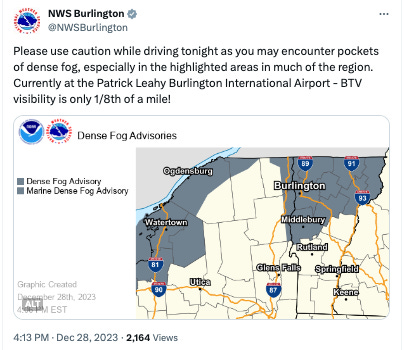

Instead, this year, just after Christmas, as it warmed again a massive fog gripped the Northeast—I took a long, wet walk in it, down to the Hudson River. You couldn’t see far. Dense fog advisories all through the region. Visibilities of 1/4 mile or less in central Vermont—apparently worse in the Champlain Valley. Fog as thick as we saw in Lubec, Maine this summer, or in northern California last year.

This intermediacy of water seems a defining, perpetually unsettled feature of climate change now in the wet Northeast… I see water fall in forms I didn’t know existed: clumpy bits of snow that look like styrofoam; thicky heavy globs of wet snow, thicker and wetter than I knew snow could get; insane snow squalls that lead to whiteouts and dump inches in a matter of minutes; hail, hail of all shapes and sizes; water vapory air so thick it feels like you’re underwater.

As a precipitation lover it fascinates me but it can be slightly terrifying. You see what the Earth can loose. Reminds me of this story about storms in Argentina a couple years ago:

The storm descended quickly. It engulfed the western side of Berrotarán, where winds began gusting at over 80 m.p.h. Soon, hail poured down, caving in the roof of a machine shop and shattering windshields. In 20 minutes, so much ice had begun to accumulate that it stood in the street in mounds, like snowdrifts. As the hail and rain continued to intensify, they gradually mixed into a thick white slurry, encasing cars, icing over fields and freezing the town’s main canal. With the drainage ditches filled in and frozen, parts of the town flooded, transforming the dirt roads into surging muddy rivers. Residents watched as their homes filled with icy water.

Meanwhile I’ve decided to maybe loosen up the format of this newsletter as we go into this new year to afford more flexibility about the experience of living through this...

And so, goodbye to 2023, the hottest year humans have yet experienced on Earth—but barring nuclear winter or geoengineering gone horribly awry, perhaps one of the coolest we will see for the remainder of our time on the planet.