Something Is Not Right

The Equinox Passes, Marking the Warmest Winter in Human History

Here’s a short one, as the high weirdness of weather in an unfolding 2024 is impossible to ignore. Now past the vernal equinox, this was likely the warmest winter on record in much if not all of the Northeast. Not that you would know this past weekend, where we just received nearly two feet of snow. If these temperatures hold, this might be one of my favorite times of year. Warming but still cool days, not-too-cold nights, snow on the ground. Out of the bitterest parts of winter, before (in theory—this year it’s been different) the ground gets too soggy and the spring ephemerals appear and then the mosquitos, the ticks, the floods or catastrophic drought or whatever else this spring and summer bring, et cetera…

This is all a change—as noted we’ve had an eerily mild winter, fog and rain and days in the fifties. It can get hard to remember; the odd thing about collectively experiencing regularly anomalous temperatures is that we seem to quickly forget—the brief but unprecedented, record-breaking heat slips amnesiatically from the mind as the climate reverts to its apparent stability, life goes on…

A couple of maps to give some impressions of where we are:

The planet had its warmest February on record, according to NOAA (to follow the warmest January on record, the warmest December, and so on…):

The February global land and ocean surface temperature was 2.52 degrees F (1.40 degrees C) above the 20th-century average of 53.8 degrees F (12.1 degrees C), ranking as the warmest February in NOAA’s 175-year global climate record…

The three-month season (December 2023–February 2024) was the Northern Hemisphere’s warmest meteorological winter and the Southern Hemisphere’s warmest meteorological summer on record, with a global surface temperature of 2.45 degrees F (1.36 degrees C) above the 20th-century average.

Looking ahead to spring and summer:

A few stories—not necessarily regional—that have caught my eye over the last few weeks:

In the Northeast, we’re seeing an uptick in severe coastal flooding happening in a handful of low-lying communities—increasingly, year-round. Below is Hampton Beach, New Hampshire, from early March:

Slightly more distantly, those Canadian fires that sent so much smoke through the Northeast and the rest of the country last year? Many are still smoldering as “zombie fires” or “overwintering fires,” with the potential to grow substantially once drier and warmer weather appears:

"A lot of people talk about fire season and the end of the fire season, but our fires did not stop burning in 2023," said [Sonja] Leverkus, who is also an adjunct professor researching wildfire at the University of Alberta.

"Our fires dug underground and have been burning pretty much all winter."

On Tuesday, Alberta called an early start to the wildfire season, 10 days earlier than usual, due to concern about the season ahead.

Are winter wildfires becoming a thing? A major wildfire in Texas in late February quickly became the largest wildfire in Texas history, at one point shutting down operations at the Pantex Plant near Amarillo, which handles nuclear weapons.

“All weapons and special materials are safe and unaffected,” [Pantex] said Tuesday evening on X.

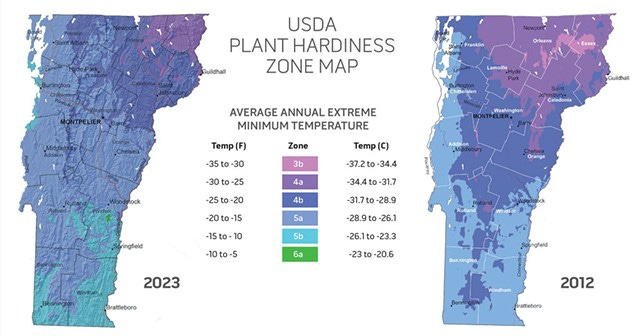

We’re now into the first growing season since the USDA adopted new hardiness zones last fall, marking a substantial change nationally from their last map in 2012. I wrote a short piece for Vermont newspaper Seven Days about this:

The latest map confirms a warming trend that Vermont gardeners and farmers have been experiencing firsthand for years. The update shows a dramatic shift across the state, with the bulk of central Vermont warming from zone 4b (minimum of -25 to -20 degrees) to 5a (minimum of -20 to -15 degrees). Parts of the Burlington area have bumped up from 5a to 5b (minimum of -15 to -10 degrees). Zone 3b (minimum of -35 to -30 degrees) has disappeared from the Northeast Kingdom, and Vermont now registers zone 6a (minimum of -10 to -5 degrees) for the first time in a few spots in Windham and Windsor counties.

In the course of doing so I found these old hardiness zone maps. My understanding is that pre-1990 these were the two dominant, not exactly competing but not identical maps, the top one from Boston’s Arnold Arboretum and the bottom one produced by the USDA. Whichever you pick (I’m partial to the first) there have been massive, invariably destabilizing changes since these were created in the sixties.

“Hardiness zones,” if we were to describe them that way, are also changing farther north. A story in Wired looks at “Arctic greening,” and the implications for the climate.

As the Arctic warms up to four times as fast as the rest of the planet, white spruce trees are now spreading into tundra that was once inhospitable. Bully for the white spruce, but not so much for the Arctic: Because the trees are darker than snow, they absorb more of the sun’s energy, potentially further heating the region and further driving dramatic change. That, in turn, could release potent greenhouse gases locked in the tundra, accelerating warming for the rest of the planet.

It’s worth reading the full story, which serves as a sort of abject lesson in feedback loops. The scientists studying the issue find a strong correlation with sea ice decline: the lower the sea ice, the more precipitation (and insulating snow) on nearby land, the faster the melting of permafrost (including the release of previously locked-up nutrients like nitrogen), and ultimately, the more rapid northward advance of the tree line. In addition to absorbing more of the sun’s energy, trees ultimately provide more fuel for wildfires, propelling the cycle even further. And things could get a whole lot worse if, as some predictions suggest, the Arctic begins to see ice-free summers in the next decade.