May–June

smoke & ticks

I don’t quite know what to make of this nearly complete spring. Here in the Northeast we’ve seen record heat and a severe late frost, days that felt like August and cool stretches when it hasn’t broken the mid-50s. To some degree things feel uncertain, that they could go in any direction this summer.

Some highlights from the last couple of months, before amnesia sets in: the tree canopy came in, as always astonishingly fast. Suddenly everything green and rocketing up. The cultivated plants (daffodils, tulips, irises, daylilies, mountain cornflower, phlox, hydrangea, and so on) and the many many more uncultivated plants springing to life in the rapidly lengthening days.

But the overall warmer weather has brought some unwelcome changes too.

ONE: In early June, the big story in the Northeast was the massive plume of wildfire smoke that moved through the region, and which produced the worst recorded air quality seen in New York City’s history.

This is, as anyone who’s lived in this region knows, completely without precedent: we’ve seen hazy skies from distant wildfires in recent years, but never an AQI of 484.1 This felt very sudden and difficult to process.

The source of the haze and smoke was an extraordinary number of wildfires burning in Canada, which have already made 2023 the country’s worst wildfire season on record. The particular heavy band of smoke came from Quebec, which, as this article describes, is facing novel conditions—almost certainly exacerbated by industrial logging:

With three months left in Canada’s wildfire season, blazes have already scorched more than 10 times the acres of land burned by this time last year. The size and intensity of the fires are believed to be linked to drought and heat brought on by a changing climate.

Fires are burning in forests in all of Canada’s provinces and territories, except the province of Prince Edward Island and Nunavut, a northern territory that sits above the tree line, where temperatures are too low for trees to survive…

…A combination of factors, fire officials said, laid the groundwork for the spread of wildfires in the Chibougamau area [in central Quebec]: freezing rain that weighed down trees and littered the forest floor with broken branches that became tinder; and unusually dry ground because snow melted earlier than usual and there was little rain in the spring.

I wrote in the first issue of this newsletter about fire season in the Northeast historically:

In the continental United States wildfires may be more loudly a Western story, but they are not necessarily confined to the West. Here in the Northeast wildfire risk tends to be particularly high in early–mid-spring, April and May, when snow cover disappears and before trees have leafed out. Indeed, in 1963, almost 200,000 acres in New Jersey burned in April. But the fire season technically lasts until winter, and fall can be bad too, especially if the summer’s been dry. In fact, one of the largest wildfires in recorded Northeastern history occurred in October of 1947, burning over 200,000 acres in Maine.

When I wrote that, I certainly had no idea we would see this sort of smoke so soon. And let’s remember, as of now, in the Northeastern United States, it’s just smoke. As they’re finding out in Quebec, that can change. The risk of that may be particularly acute if the preliminary drought we’re in worsens in the next couple of months.

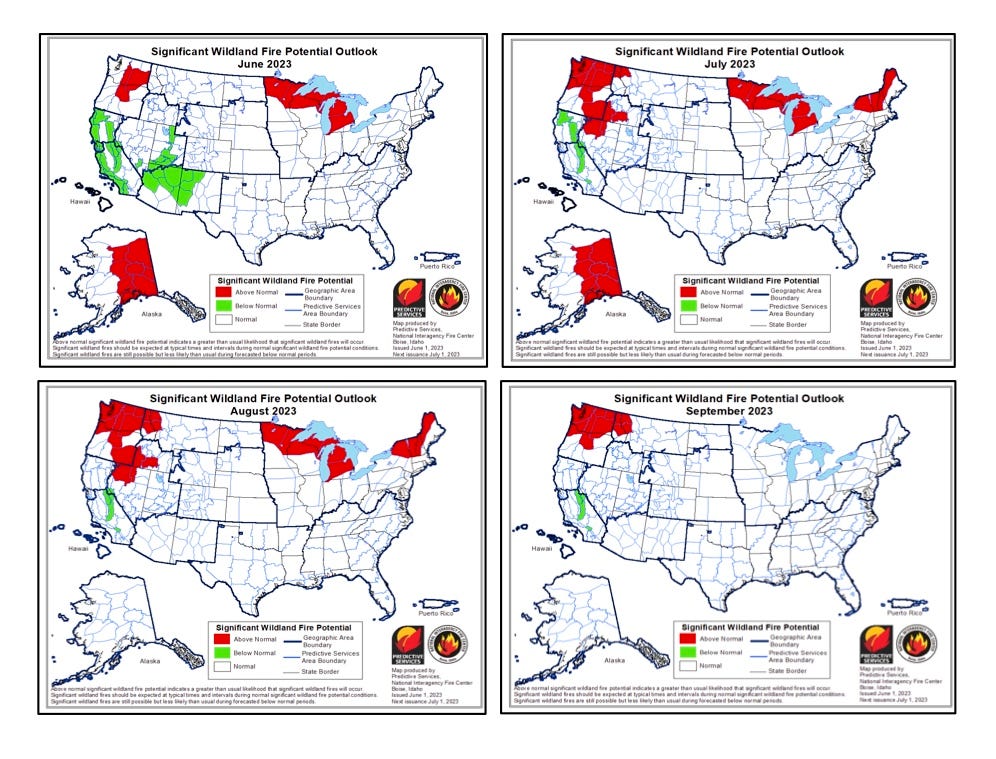

In fact, the National Interagency Fire Center warns of above-average wildland fire potential in July and August in the northern Northeast:

Outlooks show chances of above normal temperatures for this area in June, July, and August. In the absence of normal precipitation through the summer, above normal significant fire potential is forecast in July and August. Near normal significant fire potential is expected across the majority of the Eastern Area through summer into early fall. Above normal significant fire potential is forecast over the northern and eastern tiers of the Great Lakes into June and across much of the northern tier of the Eastern Area July into August.

One factor in all of this could be the formation of El Niño, the periodic higher-than-average surface temperatures that form in the Equatorial Pacific Ocean and influence global weather patterns. From the linked Axios article:

“The global oceans are very warm right now and I’m afraid that this is putting us into territory that we don’t have much experience with,” Michelle L'Heureux, chief of Climate Prediction Center's El Niño-Southern Oscillation team, said in an interview.

It seems likely that this year, or next—or, I suppose, both—will be the hottest year ever recorded by humans, surpassing 2016. In any event, while the smoke’s gone for now, these blazes in Canada won’t disappear anytime soon—so we may be seeing more smoke this summer.

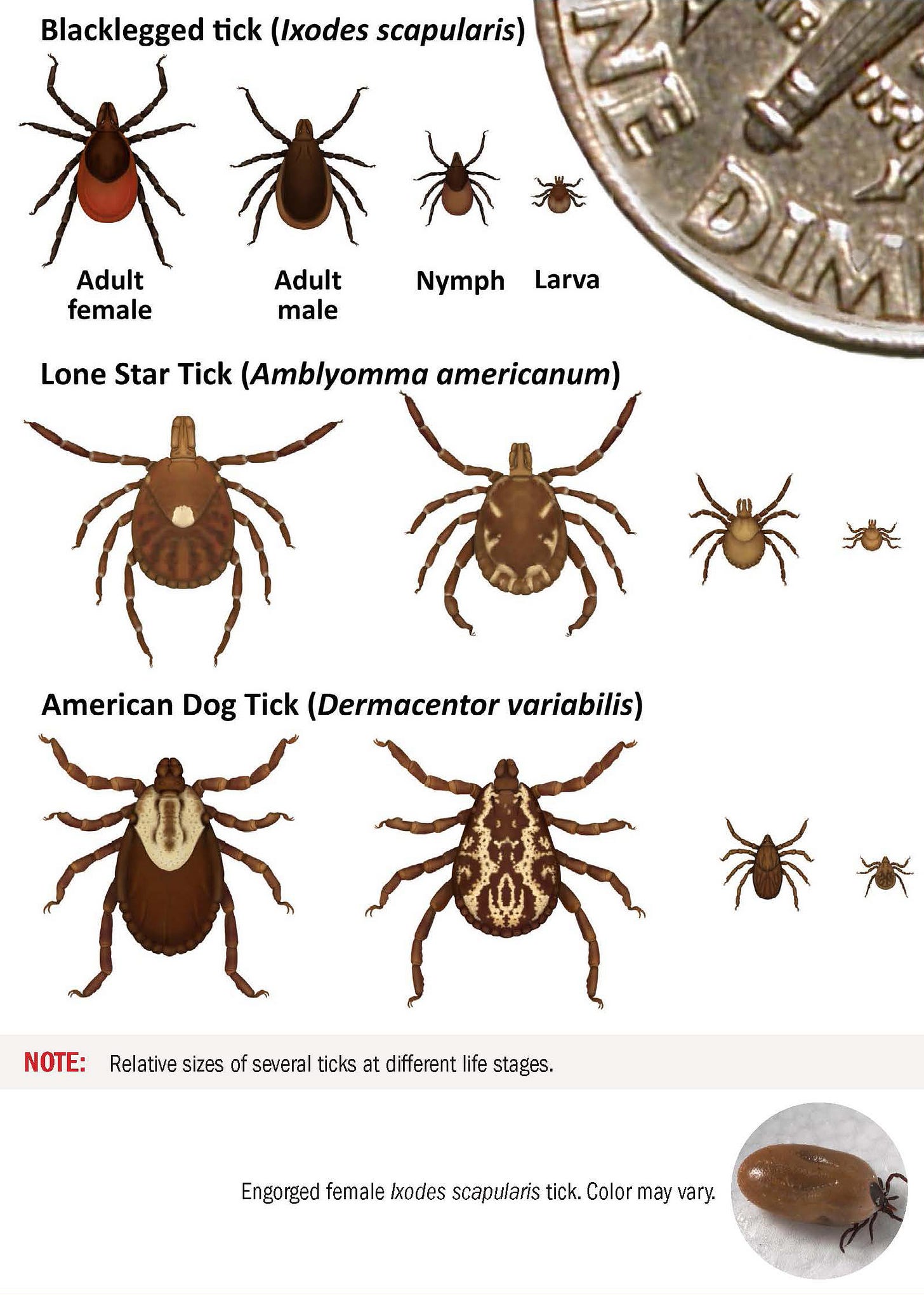

TWO: Spring tick season has been terrible this year, probably the worst I’ve ever experienced. The vast majority we’re seeing in central Vermont are American dog ticks, whose population, around here at least, seems to have exploded. (Curious about others’ experiences—sound off in the comments.)

Ticks are, obviously, not a new story in the Northeast. But they are a changing one. Since its identification in 1975, Lyme disease, which is transmitted by the blacklegged tick, has spread substantially through the region.

But the story around ticks has gotten even more disturbing in recent years. Blacklegged ticks spread an increasing number of other diseases—anaplasmosis, babesiosis, and others—while new ticks and new diseases have also shown up in the Northeast.

One of these diseases is Powassan virus, which is spread by the blacklegged tick, can be fatal, and is appearing more regularly in the Northeast. From the Yale School of Public Health:

Sometime between 1940 and 1975, a major branch of the lineage 2 virus appeared in the Northeast. This branch of the virus, which accounts for most Powassan cases in North America, first appeared in southern New York State and Connecticut. Then, several long-distance jumps occurred, likely when infected ticks caught rides on migrating birds or other vertebrate hosts. By 1991, it had reached Maine. During its initial decades in the region, Powassan became more populous in the wild, but this probably leveled off about 2005.

The virus now appears to be moving slowly or staying put, simmering in specific hotspots, and evolving independently in each one. For instance, the scientists could find no evidence that separate clades of the virus were mingling with each other across a 20-kilometer (or approximately 12.5 miles) stretch between two Connecticut sites. The scientists note, however, that they sampled only a limited number of locations, so it’s possible they missed hotspots.

And then there’s the lone star tick, a Southern migrant increasingly found in the Northeast. They get their name from the white dot adult females have on their backs, and, in addition to ehrlichiosis and other diseases, they may cause alpha-gal syndrome, which causes an allergy to red meat.

Thus far, however, this has been the year of the dog tick. The American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis) is, in theory, preferable to the blacklegged tick. They do not spread Lyme, and while they can transmit tularemia and Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, this appears to be pretty rare up here.

But they have been incessant—we’ve picked multiple off ourselves and our dog pretty much every day for at least a month.

For some more information on what’s affecting tick spread, I recently spoke to Dr. Shannon LaDeau, a disease ecologist at the Cary Institute in Millbrook, New York.

Dr. LaDeau and I talked for an article I wrote for the Times Union last month about the impacts of last year’s drought in New York’s Hudson Valley, but much of what she said didn’t make it into that story, so I’m including a little more of her commentary here.

Among other things, I was curious how last summer’s drought might be affecting tick populations now. From LaDeau:

“[Ticks] don’t drink, which means they have to absorb water from the air, so low humidity is definitely a deterrent or a negative impact on tick survival. Ticks normally get around this by just hanging out in the leaf litter, where the soil moisture… keeps humidity higher than the air.”

Basically, she explained, during drier periods, ticks may end up spending less time looking for a meal, fail to find one, and die for that reason; or they may stay out too long looking for food, and dry out and die for that reason.

LaDeau also explained how the timing of a tick’s life stages can intersect with drought to impact population survival:

“Tick survival is definitely affected by long droughts if they occur at the time of year when the ticks are looking for blood meals. In the Northeast, that tends to be three different times a year, clustered around the different life stages.”

These three stages are, she explained, the larval stage (in spring), the nymph stage (in late spring and early summer), and the adult stage (in late summer and early fall). Likely, she said, the timing of last year’s drought affected tick survival during the nymph and adult blood meal phases.

I was also interested in the impacts of the mild 2022-23 winter. In my experience, people tend to assume that deep cold kills ticks—but turns out that’s not exactly correct.

LaDeau told me that “ticks don’t really seem all that affected by winter conditions,” as they can burrow down into the soil and are adapted to freeze.

The survival of other animals, though, is important. Mice and small mammals are less likely to make it through a harsh winter and may have shorter periods of activity, reducing their availability to ticks and potentially limiting blood meals. The same thing can actually happen in droughts, which can also adversely impact small mammal survival and, consequently, reduce tick populations.

As far as this spring, LaDeau told me it was too early to have clear data on how these climatic factors have affected ticks. But she (like pretty much everyone else) told me that she’s found plenty of ticks on her already this year, suggesting any lasting decreases in tick populations from last year’s drought are unlikely.

(Thank you to Dr. Shannon LaDeau for OKing the use of this material here. Check out her work at the Cary Institute and on Twitter.)

FURTHER READING

On drought and water quality:

As mentioned, last month I wrote for the Times Union about 2022’s record-setting drought in the Hudson Valley (a drought that affected the entire Northeast and was actually worst closest to the coast). I spoke at length to Dan Shapley of the environmental advocacy organization Riverkeeper about water quality and conservation efforts in the region:

[Shapley] wants to see communities start thinking more about the intersection between drinking water quality and climate change. “It’s fair to say that the Hudson Valley is really leading in the state on the community level in planning for climate adaptation,” he said, pointing to the Climate Smart Communities Program, and the Drinking Water Source Protection Program.

But the link between those two areas has to be clearer, Shapley said.

“We need to get those two programs really synced up and help communities understand that there will be changes to their drinking water supply from climate change. Right now, there’s just a disconnect between those two really important spheres of planning.”

On May’s hard frost and fruit crops:

Fruit growers in Vermont suffered mightily from May’s late cold snap, as explained in this VTDigger story:

“A frost in May is not unheard of, but this one was significant enough because it was so cold,” Vermont’s Secretary of Agriculture Anson Tebbetts told VTDigger this week. “And the particular timing — the apples were in bloom, the blueberries were in bloom, very tender vines for the grapes — everything was really vulnerable.”

Much of the damage was immediately visible. On the morning of May 18, farmers could split open their apple buds and find brown inside, a sure sign of death for the young fruit. But weeks later, a fuller picture of the frost’s impact is coming into focus.

Along with colleagues at the state Agency of Agriculture, staff with the University of Vermont Extension surveyed fruit tree farmers across the state. Nineteen apple orchards responded, accounting for roughly half of the state’s acreage. “For the vast majority of respondents, estimated crop loss was 95% or greater,” Tebbetts told VTDigger.

On ticks (and mosquitos):

My first conversation with Dr. LaDeau was in late 2021, when I spoke with her—and two other scientists—about the spread of tick and mosquito-borne diseases for a story in The River. It is a disturbing area of research, and while climate change is a big factor, patterns of human development are possibly even more significant.

Scientists who study the spread of diseases from wildlife to humans agree that it is becoming more of a problem, but their understanding of the expansion process is still limited. “It is really difficult to identify a single factor responsible for the increases in vector-borne diseases that we are seeing,” says Dr. Laura Harrington, director of the CDC Northeast Regional Center for Excellence in Vector-Borne Diseases.

Harrington recognizes a combination of factors, including climate change, range expansion, globalization, and inadequate education and public health messaging. The spaces where these variables intersect pose the greatest challenges for scientists and contemporary modeling—and prevention—efforts.

[Dr. Maria Diuk-Wasser] points to the reforestation of the Northeast over the last century, coupled with increased suburbanization of areas where deer and other animal populations roam widely, as creating a “perfect storm” for spread of tick-borne diseases. But even this fails to fully capture at the micro level where and why spread is increasing—and what is to be done about it. LaDeau notes the difficulty of “trying to capture both the human behavior and built infrastructure components, and the interactions with climate,” to effectively understand limits on vector and pathogen spread.