Earlier this summer I took a pretty extraordinary trip to the easternmost tip of Maine. The weather for the most part was beautiful—daily highs didn’t exceed 70° F, and cool, foggy nights near the maritime spruce-fir forest dipped into the high 50s—an otherworldly respite from typical summer heat.

But those few days I was away also happened to be, on average, the hottest in Earth’s recorded history.

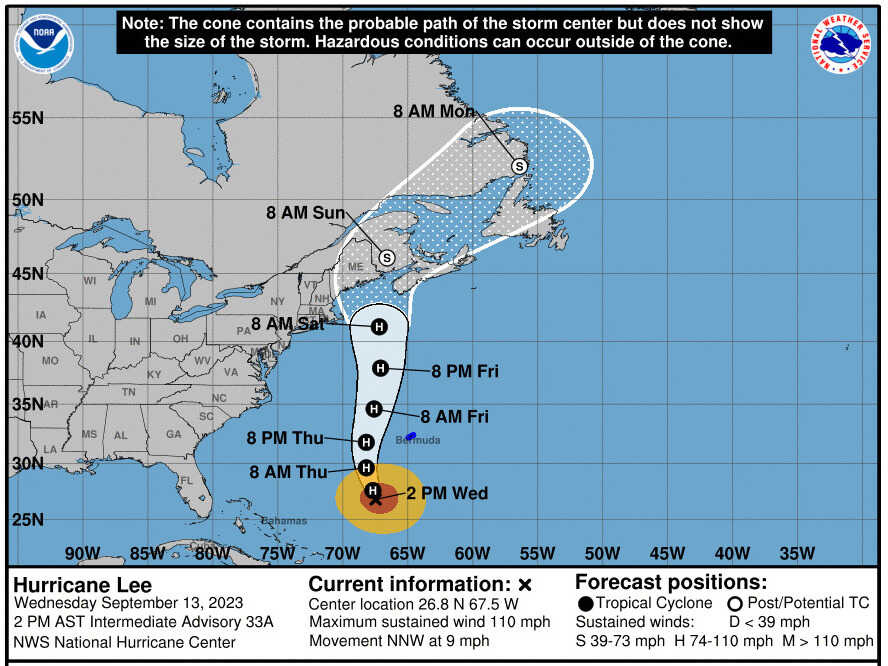

I’m thinking about this again as we pass out of an early-September heat wave in the Northeast, and as Hurricane Lee rotates in the Atlantic—likely heading to that very same part of Maine—on the heels of an especially cool August. While I’ve been glad to get in the cold, high, now-clean White River (the longest free-flowing river in the state of Vermont) I’ve also been disturbed by these record-breaking temperatures.

Some effects of global heating this summer: wildfires burning in Canada and the consequent smoke and haze here; many tornadoes along with torrential downpours spawned by severe storms throughout New England; terrible, unrelenting mosquitos—and more distant phenomena, like the longest uninterrupted sequence of 110° F+ days in Phoenix, Arizona’s history; heat so blistering in Sicily it melted underground power cables; a “medicane”1 deluging Greece’s agricultural heartland before collapsing two dams and killing thousands in Libya; the horrific wildfire disaster on the Hawaiian island of Maui, the worst nationally in over a century; possibly the magnitude 6.8 earthquake in Morocco2); and on and on…

Both cause and consequence of global heating has been the record-warm global ocean, including our very own North Atlantic Ocean.

Via AFP, from late July:

On the heels of a new record high in the Mediterranean, the North Atlantic reached its hottest-ever level this week, several weeks earlier than its usual annual peak, according to preliminary data released Friday by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The news comes after scientists confirmed that July is on track to be the warmest month in record history—searing heat intensified by global warming that has affected tens of millions of people…

“This situation is extreme: we've seen maritime heat waves before, but this is very persistent and spread out over a large surface area” in the North Atlantic, Karina Von Schuckmann from the Mercator Ocean International research center told AFP… On a global scale, the average ocean temperature has been besting seasonal heat records on a regular basis since April.

This was not unexpected. The oceans have absorbed 90% of human-caused global heating, heat that has produced a steady rise in ocean temperatures since the late 1960s—along with sea level rise, as heat in the ocean leads water to expand.

North Atlantic oceanic heat is also causing the Northeast to warm faster than the rest of the planet, particularly in areas closest to the ocean (in Rhode Island, for instance, temperatures have risen nearly 4° F in the last century).

While the water in Maine felt chilly in early July, it was historically abnormal: a critical factor in regional warming is the uniquely extreme rise in temperatures in the Gulf of Maine, one of the fastest-warming bodies of water on the planet.

“There’s a gradual [warming] trend that we’ve had in the Gulf of Maine that’s about four times the global average rate, but a lot of our warming has occurred since 2004,” Andy Pershing, Ph.D. (and at the time, chief scientific officer at Gulf of Maine Research Institute) says in the video above. “From 2004 through 2016, we warmed faster than 99% of the global ocean.”

According to Pershing, the causes of the Gulf of Maine’s unique warming are anthropogenic climate change, Arctic melting, and shifts in ocean circulation. The Gulf’s position in the North Atlantic is unique, and shifts in freshwater content caused by melting Arctic and Greenland ice have outsized impacts.

The video above was produced in 2018, but the currents Pershing refers to made headlines this summer when a July study in Nature Communications warned about the potential collapse of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC), the Atlantic current system that brings warm, tropical waters north and cold, Arctic waters south.

“We estimate a collapse of the AMOC to occur around mid-century under the current scenario of future emissions,” and possibly as soon as 2025, the study’s authors wrote.

There is considerable uncertainty in such modeling—and in this case, in whether total collapse versus continued weakening is more likely. But the breakdown of AMOC would be catastrophic. It would likely lead to extraordinary cooling in Europe (and possibly parts of the United States), major shifts in precipitation in the tropics, and rapidly rising sea levels in the North Atlantic. This, of course, underplays the functionally apocalyptic effects of such impacts, given global food production, existing migration patterns, and so much more—including effects we don’t yet understand.

It’s worth remembering that we’re not passively experiencing these impacts; we are actively making them happen, and—whether the outcome is this catastrophic or not—radical social, economic, and political changes are the only “remedy.” Like it or not, those changes are coming one way or another.

FURTHER READING

On those incessant mosquitos… Mosquito-borne illness continues to be a major hazard in the Northeast. I wrote about this in The River almost two years ago:

Two mosquito-based pathogens stand out as particular concerns: West Nile virus and Eastern equine encephalitis. Both have existed in the Northeast for a long time: EEE’s identification dates back to the 1800s, while West Nile first appeared in the United States about two decades ago. Both are also fairly rare, at least in severe cases, but as [Dr. Shannon] LaDeau explains, a lot is unclear due to a lack of testing. If mosquito populations rise, the risk of West Nile and EEE should also rise. “It’s fair to assume that if you have more of those vectors, you will have a higher risk of human disease outbreak,” she says. “But that’s a pretty coarse target,” and does not consistently explain the reality on the ground.

Eastern equine encephalitis risk is currently classified as “high” in several central Massachusetts towns, and has also been found in at least Vermont, Rhode Island, and Connecticut this year. West Nile Virus has been found in all New England states, as well as New York.

(Slightly) farther away, locally acquired malaria cases appeared in the United States this year for the first time in two decades. Notably, one of those cases occurred relatively far north, in Maryland:

“Malaria was once common in the United States, including in Maryland, but we have not seen a case in Maryland that was not related to travel in over 40 years,” said Maryland Department of Health Secretary Laura Herrera Scott. “We are taking this very seriously and will work with local and federal health officials to investigate this case.”

On the extreme ocean temperatures… Recent weather news in the Northeast has focused on the possible impacts of Hurricane Lee, which now looks like it will make landfall somewhere in Maine or Atlantic Canada—though impacts should be significant on the New England coast and possibly further inland.

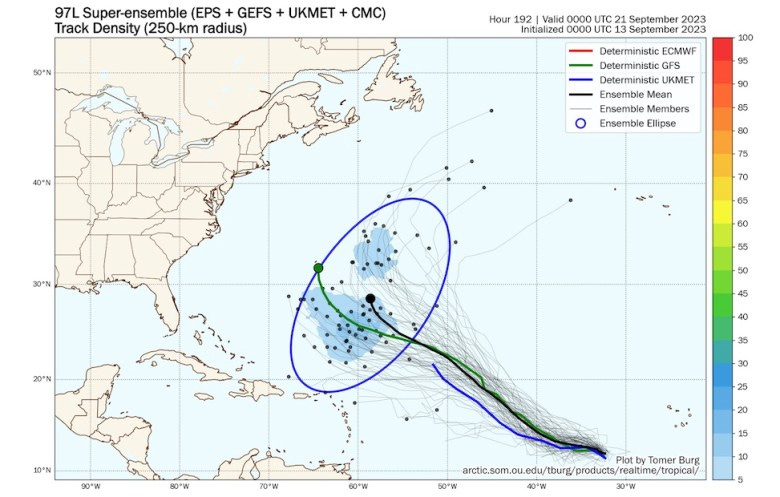

While Lee has gotten the bulk of recent attention, a tropical disturbance in its wake is worth watching:

A disturbance dubbed Invest 97L in the eastern tropical Atlantic, located several hundred miles west-southwest of the Cabo Verde Islands Wednesday afternoon, will likely become the next Atlantic system of interest. The disturbance had a moderate amount of spin and was generating heavy thunderstorms that were becoming increasingly well organized… The next name on the Atlantic list is Nigel… given that any westward bend or ultimate recurve is a week or more away, it is too soon to predict the longer-term fate of 97L with confidence.

A “medicane” is a traditionally rare Mediterranean cyclone; a 2007 paper in the journal Geophysical Research Letters predicted an increase in such storms due to climate change.

It might seem like a stretch to attribute the earthquake in Morocco to global heating and I’m not enthusiastically making the claim—the Atlas Mountains are seismically active and a serious earthquake in 1960 killed 15,000 people. However, there does appear to be some evidence of a link between climate change and earthquakes, which may have to do with melting ice caps and a consequent shift in pressure on tectonic plates—though officially scientists say we shouldn’t be seeing impacts yet.